This was our final Networking report paper during my master’s degree in Information Security (InfoSec) that we did not try to publish. The topic and initial router configurations were presented by my group mate, E.C. However, I had to make some changes to the provided router configurations and network architecture to remediate the issues we faced in the lab. I deployed the lab environment and revised router configuration using GNS3, then wrote our report paper, which you see now below. I decided to post this in my personal blog since there are limited resources out there relating to this topic and the hope that this will fill in certain knowledge gaps. As a matter fact, I had troubles researching and understanding certain concepts because of this limitation.

Abstact

This study aims to explore and demonstrate the implementation of virtual routing and network address translation (NAT) using RFC 6598 Shared Address Space (100.64.0.0/10) to overcome private Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) address overlaps in large business-to-business (B2B) network interconnections. This study emulates a simplified network of two interconnecting business entities using GNS3. A container appliance deployed on each business entity’s internal network has an IPv4 address in an overlapping range of 10.22.0.0/16. The emulated edge router without virtual routing and NAT cannot route to the remote business entity’s network since a connected route entry to the same address range already exists. A virtual router (VRF), provisioned on the emulated edge router, acts as the next hop for traffic destined for the overlapping remote network. In addition, the VRF performs all NAT operations. Established tunnels using loopback interfaces link the virtual router and the global router. Underlay and overlay routing create connectivity between the global router, VRF, and the overlapping remote network. Results show reachability between the two container appliances in the overlapping network using Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) Ping and Traceroute after implementing virtual routing and NAT on the emulated edge router. The NAT Translation Table on the emulated edge router confirms the mapping of the 10.0.0.0/8 private address to the 100.64.0.0/10 shared address space. Further research is needed when implementing on a different vendor device due to proprietary features and configuration commands.

Introduction

Over the years, the rapid exhaustion of Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) led to the development of private IPv4 addressing and Network Address Translation (NAT). RFC 1918 defined the Private IPv4 Address Space as a list of reserved addresses used for intra-enterprise communications [1]. NAT, defined in RFC 3022 [2], allows a host that does not have a valid, registered, and globally unique IP address to communicate with other hosts through the Internet by mapping the private address to a publicly routable address and vice versa [3]. Different address mappings can also occur in NAT; one example can be translating an RFC 1918 address to an RFC 6598 address as demonstrated in this paper (post). NAT and private IPv4 addresses allow entities to reuse the same space for their internal networks.

According to Harvard [4], the total Merger and Acquisition (M&A) deal volume in 2021 increased by more than 60% relative to the $3.6 trillion recorded total deal volume in 2020 – a record-breaking activity. As businesses grow, connections and acquisitions occur to achieve synergy. Large organizations commonly use the 10.0.0.0/8 address space to accommodate the number of sites, subnets, and hosts while having enough room for growth. Connecting large business entities due to M&As having the same address range (i.e., 10.0.0.0/8) will not be able to establish proper network communications due to IPv4 address overlaps. The edge router will not be able to route to the remote network because a connected route entry to the same address space already exists in its routing table. A different business size using other address spaces (i.e., 172.16.0.0/12 and 192.168.0.0/16) can encouter a similar problem when merging with a remote network using the same private address range.

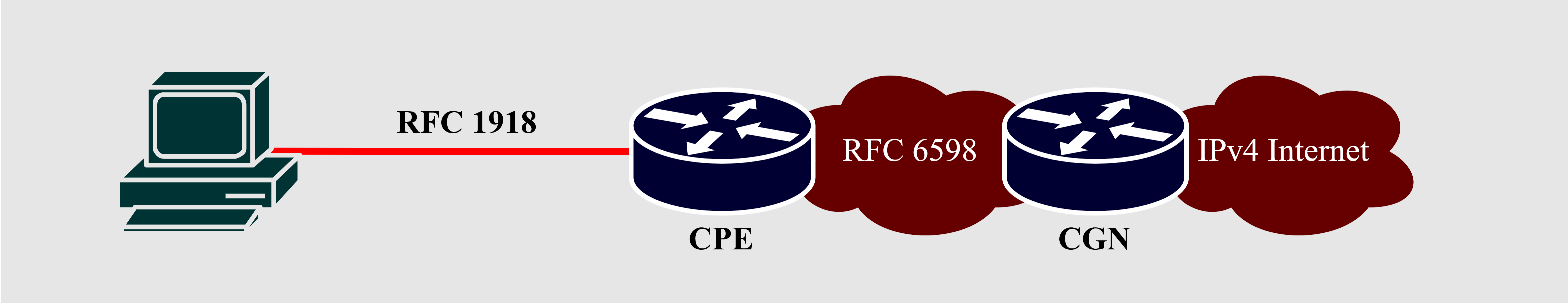

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) allocated the 100.64.0.0/10 address block defined in RFC 6598 [5] as a non-globally routable Shared Address Space intended on the Service Provider (SP) networks or routing equipment capable of address translation across router interfaces having identical addresses on two different interfaces. The Shared Address Space enabled SPs to support IPv4 growth until the full deployment of Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) by using the 100.64.0.0/10 address block on the interfaces of Carrier-Grade NAT (CGN) devices connecting to the Cusomter Premises Equipment (CPE). Although it is possible to allocate the Shared Address Space to hosts in the private network when no RFC 1918 address is available, it increases the probability of address conflicts towards the SP network. Furthermore, it strays from the true intent specified in RFC 6598. Fig. 1 shows a sample SP topology leveraging the RFC 6598 addresses.

Fig. 1. RFC 6598 SP Topology

Fig. 1. RFC 6598 SP Topology

According to Google’s IPv6 adoption statistics [6], the availability of IPv6 connectivity among Google users globally did not surpass 40% as of late 2022 since the beginning of the data in 2008. In addition, based on W3Tech survey [7], as of 2022, only 21.5% of websites use IPv6. IPv6, introduced in 1995, serves as a replacement protocol for IPv4 [8]. Even with the improvements that IPv6 brings, such as having a larger address space that supports 3.4x10^38, compared to 4.3 billion IPv4 unique addresses. Expensive infrastructure, no direct benefits for early trendsetters, adn end-user tech incompatibility contribute to the global adoption of IPv6 [9]. For these reasons, enterprises still run solely IPv4 in their network or as a dual-stack configuration.

With the depletion of IPv4 and the slow adoption of IPv6, merging business entities using the same private IPv4 address space will need a solution for their overlapping addresses. This study aims to explore and demonstrate the implementation of virtual routing and network address translations (NAT) using RFC 6598 Shared Address Space to overcome private IPv4 address overlaps in large business-to-business (B2B) network interconnections.

Network Addressing Scheme and Address Conflicts

One of the considered best practice implementations of the IPv4 addressing scheme leverages the three RFC 1918 address blocks, 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, and 192.168.0.0/16 for special-use networks [10]. The 10.0.0.0/8 used in internal networks allocates the second octet of the address to distinguish the enterprise’s various sites (branch offices, data center, or VPN hub). The third octet of the address segments the site’s network into smaller subnetworks (subnets). The fourth and final octet of the address identifies the individual hosts residing in the specified subnet. The remaining address blocks, 172.16.0.0/12 and 192.168.0.0/16 are often used in Wide Area Network (WAN) links and Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), respectively. Note that the RFC 1918 does not mandate the specific use of each address block; the usage of each block can depend on the business requirements as long as used internally.

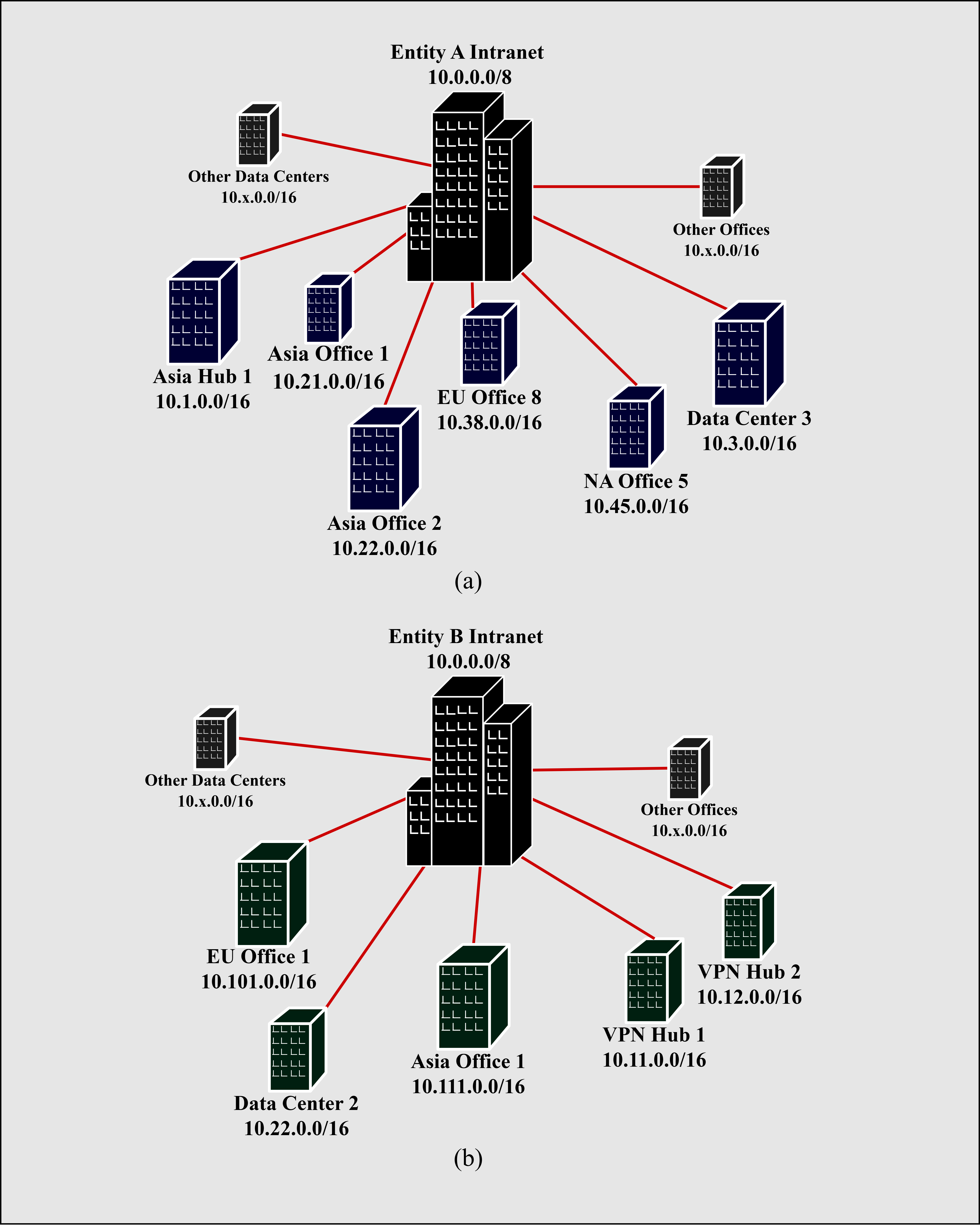

Fig. 2. (a) Entity A Addressing Scheme (b) Entity B Addressing Scheme

Fig. 2. (a) Entity A Addressing Scheme (b) Entity B Addressing Scheme

This study concentrates on two sampled enterprises, Entity A and Entity B, illustrated in Fig.2 (a) and (b), respectively. The sampled entities are global enterprises with thousands of employees across their sites throughout Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Both entities use the 10.0.0.0/8 Class A private network for their global intranet. The addressing scheme assigns a /16 network on each site; the second octet, 10.x.0.0/16, distinguishes the sites; this can accommodate 256 (2^8) total sites. In Fig. 2, the “x” in the 10.x.0.0/16 represents omitted sites for simplicity. The third octet further segments the /16 network of each site into a /24 subnet; each site can have 256 (2^8) separate subnets. For example, in Asia Office 2 (10.22.0.0/16) of Entity A, the Development VLAN can be assigned in the 10.22.0.0/24 subnet. Each subnet can allocate the remaining octet to identify the hosts; each subnet can have 254 hosts (2^8-2). The first IP address in the subnet, in this example, 10.22.0.0, identifies the subnet, and the last IP address, 10.22.0.255 in this example, acts as the broadcast address. A well-known practice seen throughout the Information Technology (IT) industry allocates the first usable IP address of the subnet to the default gateway; this can also be seen in Microsoft Azure default environments [11]. Following the example above, the default gateway of the 10.22.0.0/24 subnet will have an IP address of 10.22.0.1. The remaining usable IP addresses in the subnet, in this example, addresses between 10.22.0.2 and 10.22.0.254, can be assigned to hosts in the subnet.

Interconnecting Entity A and Entity B

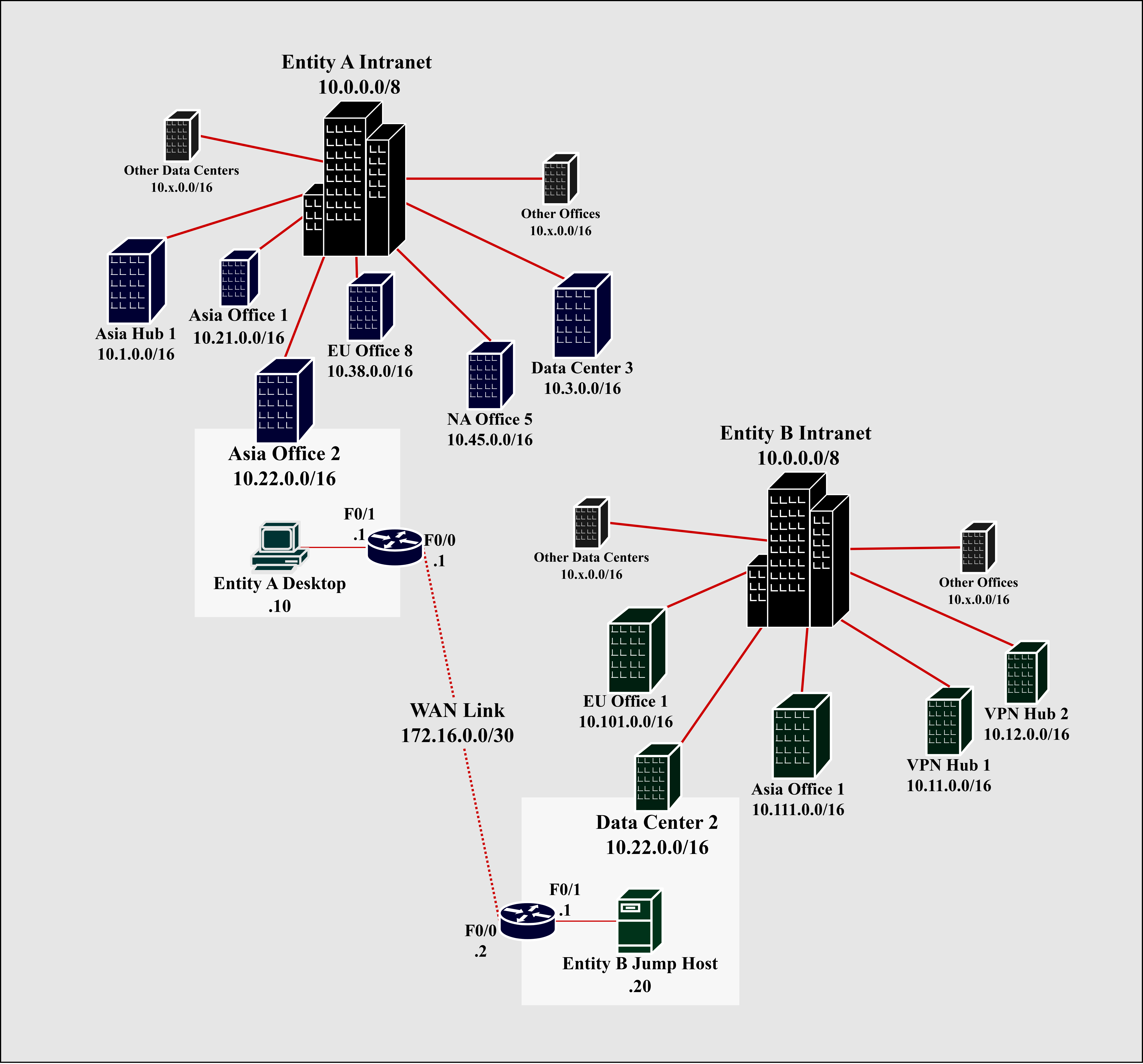

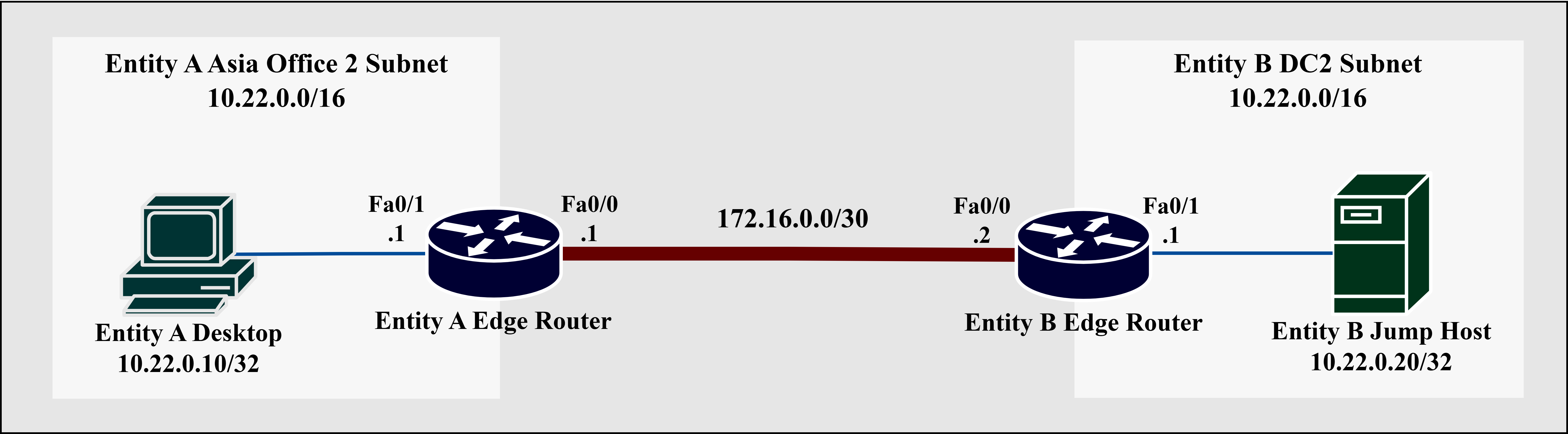

With Entity A merging with Entity B, shown in Fig. 3, their internal network will overlap since both entities use the 10.0.0.0/8 address range. As a result, the routers connecting the two entities will not be able to properly route to the remote network due to addressing conflict since a connected route entry to the same subnet already exists in their routing table.

Fig. 3. Entity A and Entity B Physical Interconnection

Fig. 3. Entity A and Entity B Physical Interconnection

This post will focus on the scenario where a desktop in Entity A’s Asia Office 2 having an IP address of 10.22.0.10 requires bi-directional communication to a jump host residing in Entity B’s Data Center 2 (10.22.0.0/16) having an IP address of 10.22.0.20. The default gateway on both subnets utilizes the first usable IP address of the subnet, 10.22.0.1. A WAN link in the 172.16.0.0/30 subnet interconnects the Asia Office 2 of Entity A and the Data Center 2 of Entity B. The WAN link can be a site-to-site IPSec VPN, GRE, point-to-point, MPLS, or SD-WAN; the interconnection type between routers does not affect the implementation of virtual routing and NAT on the edge router. Therefore, this study abstracts the WAN link interconnection between entities for simplicity.

The router deployed on both entities, running Cisco C7200 IOS, has two Fast Ethernet interfaces (F0/0 and F0/1). The WAN-facing FastEthernet0/0 interface interconnects the sites of the entities. FastEthernet0/1 faces the internal 10.22.0.0/24 subnet, acting as the default gateway.

Address Conflicts on the Routing Table

Routers select the best routes based on three criteria [8,12]: Longest Prefix Match, Administrative Distance, and Metric. The route entry with the longest (most specific) prefix takes precedence over the other criteria. For example, if a router has 10.22.0.0/16 and 10.22.0.0/24 in its routing table, a packet destined for 10.22.0.20 will be forwarded using the 10.22.0.0/24 route. Administrative Distance (AD) measures the trustworthiness of the source of the routing information [13]; the router uses the AD value to determine which routing protocol to use if two protocols provide route information for the same destination. Each routing protocol has its corresponding AD value shown in TABLE 1; the router chooses the lowest AD value when identifying which protocol to add to its routing table. When the router learns different paths to the same network from the same routing protocol, it consults the metric value to decide which route to add to the routing table. Similar to the AD, the router adds the route information with the lower metric in its routing table. The metric calculation varies from protocol to protocol; Routing Information Protocol (RIP) uses hop counts, OSPF uses a parameter called cost, et cetera.

| Route Source (Protocol) | Default AD |

|---|---|

| Connected Interface | 0 |

| Static Route | 1 |

| Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (EIGRP) Summary Route | 5 |

| External Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) | 20 |

| Internal EIGRP | 90 |

| IGRP | 100 |

| OSPF | 110 |

| Intermediate System-to-Intermediate System (IS-IS) | 115 |

| Routing Information Protocol (RIP) | 120 |

| External Information Protocol (EGP) | 140 |

| On Demand Routing | 160 |

| External EIGRP | 170 |

| Internal BGP | 200 |

| Unknown | 255 |

TABLE 1 Default Administrative Distance Values

TABLE 2 below the routing table on both entities’ routers. The router automatically adds a connected route and a local route into its routing table after enabling and configuring an IP address on the interface [8]. The router checks the line status and protocol status of the interface. The line status represents Layer-2 connectivity, and the protocol status represents the Layer-3 (IP) configuration; both must be in the UP state before the router can forward any packets [14]. The connected route designates the subnet where the interface belongs by computing the configured subnet value. While the local route entry represents a host route (/32) used to efficiently forward local traffic to the router’s Network Interface Card (NIC).

| Type | Subnet | Egress Interface | AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connected | 10.22.0.0/24 | FastEthernet0/1 | default |

| Local | 10.22.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/1 | default |

| Connected | 172.16.0.0/30 | FastEthernet0/0 | default |

| Local | 172.16.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/0 | default |

(a) Entity A

| Type | Subnet | Egress Interface | AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connected | 10.22.0.0/24 | FastEthernet0/1 | default |

| Local | 10.22.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/1 | default |

| Connected | 172.16.0.0/30 | FastEthernet0/0 | default |

| Local | 172.16.0.2/32 | FastEthernet0/0 | default |

(b) Entity B

TABLE 2 (a) Entity A Routing Table (b) Entity B Routing Table

In TABLE 2 above, the routers have identical routes for the 10.22.0.0/24 subnet. A static route to the 10.22.0.0/24 subnet of Entity B will conflict with the connected route entry. Furthermore, the router ignores the static route configuration since directly connected routes take precedence due to its lower AD value of 0. Although it is possible to create a longest prefix match static route to bypass the connected route for traffic destined to Entity B’s jump host (10.22.0.20/32), conflicts can still occur for hosts having identical IP addresses. For example, the jump host in Entity B has a static IP address of 10.22.0.10/32; a longest prefix match static route can no longer be a solution since it now conflicts with the desktop in Entity A having the same IP address of 10.22.0.10/32. Instead, virtual routing and NAT configured on the router of Entity A introduce a more scalable solution with far lesser possibility of addressing conflicts due to the use of the RFC 6598 Shared Address Space instead of a different RFC 1918 address block [15]. The reason is that IANA did not intend to allocate the RFC 6598 Shared Address Space to hosts in the private network. The proposed solution will require minimal configuration on the router of Entity B. It will only need a routing entry to the translated address of Entity A. Making it viable for entities with limited access and control over the merging network devices. Furthermore, Virtual routing (VRF) and NAT are features available in most enterprise-grade routers used by global entities, minimizing cost when implementing this solution.

GNS3 Emulated Environment

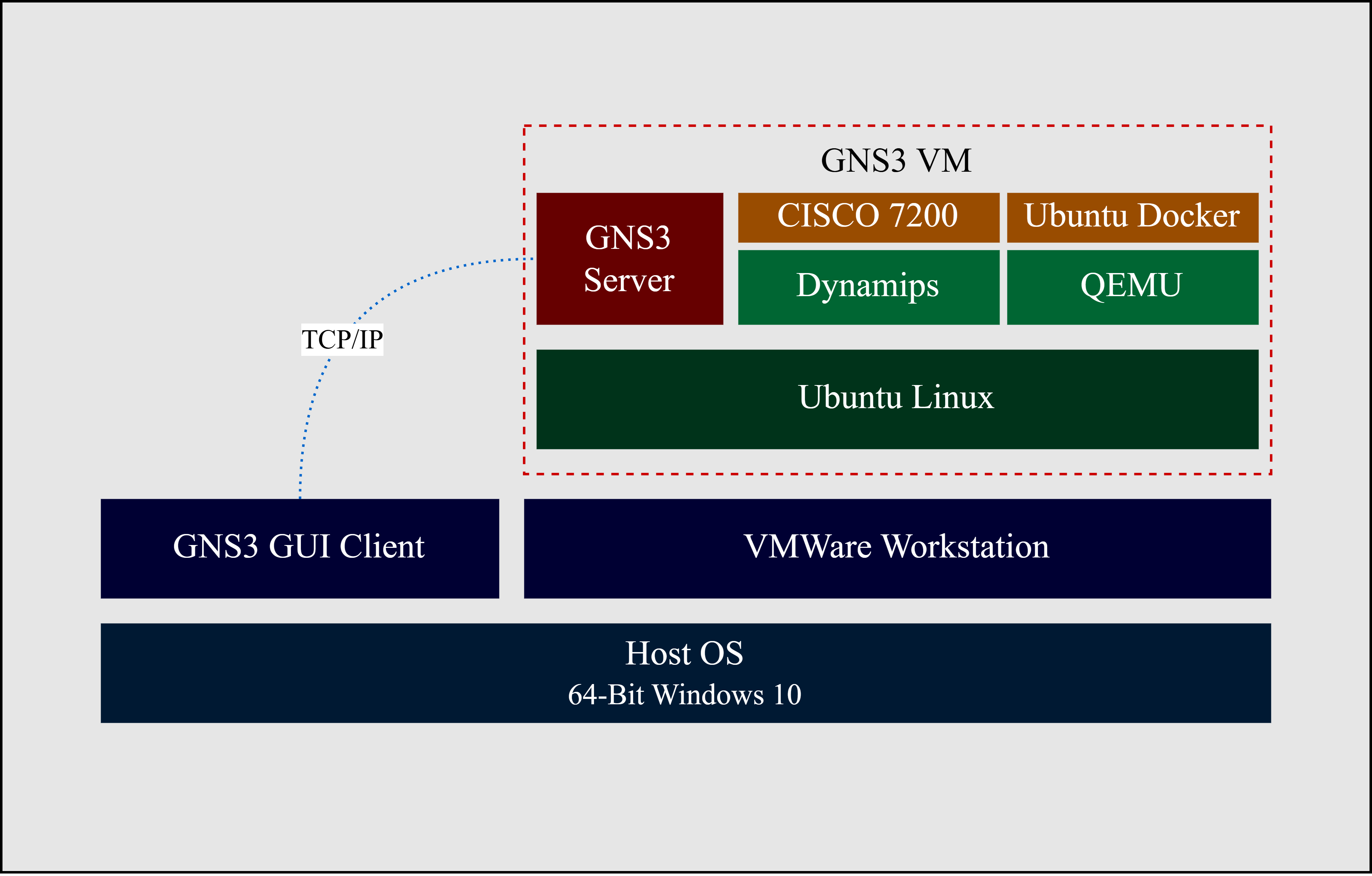

The Graphical Network Simulator-3 (GNS3) is an open-source network emulator used by thousands of network engineers and many large companies worldwide, including Fortune 500 companies, to emulate, configure, test, and troubleshoot virtual and real networks [16]. GNS3 consists of two main components: the GNS3-all-in-one software (GUI) and the GNS3 virtual machine (VM).

The GNS3-all-in-one software is the client graphical user interface (GUI) component of GNS3 installed in the host device (Windows, MAC, or Linux) that allows users to create network topologies. The devices deployed in the GNS3-all-in-one software require a host server to run. GNS3 supports three options for its server: local GNS3 server, local GNS3 VM, and remote GNS3 VM.

Fig. 4. GNS3 Architecture

The local GNS3 server runs locally on the same host device as the GNS3-all-in-one software. The GNS3 VM can either be run locally on the host device using virtualization software like VMWare Workstation, VirtualBox, or Hyper-V; or provisioned remotely using VMWare ESXi or the cloud. This study selected the local GNS3 VM, as recommended by GNS3, to emulate the Cisco 7200 IOS using Dynamips, a MIPS Processor emulation program [17], and Linux Ubuntu container through QEMU, a generic and open-source emulator and virtualizer. Fig. 4 shows the GNS3 architecture in this paper; the GNS3 VM, running Ubuntu OS, runs on the VMWare Workstation hypervisor. The host device is a 64-bit Windows 10 laptop.

Network configuration

(a)

(a)

(b)

(b)

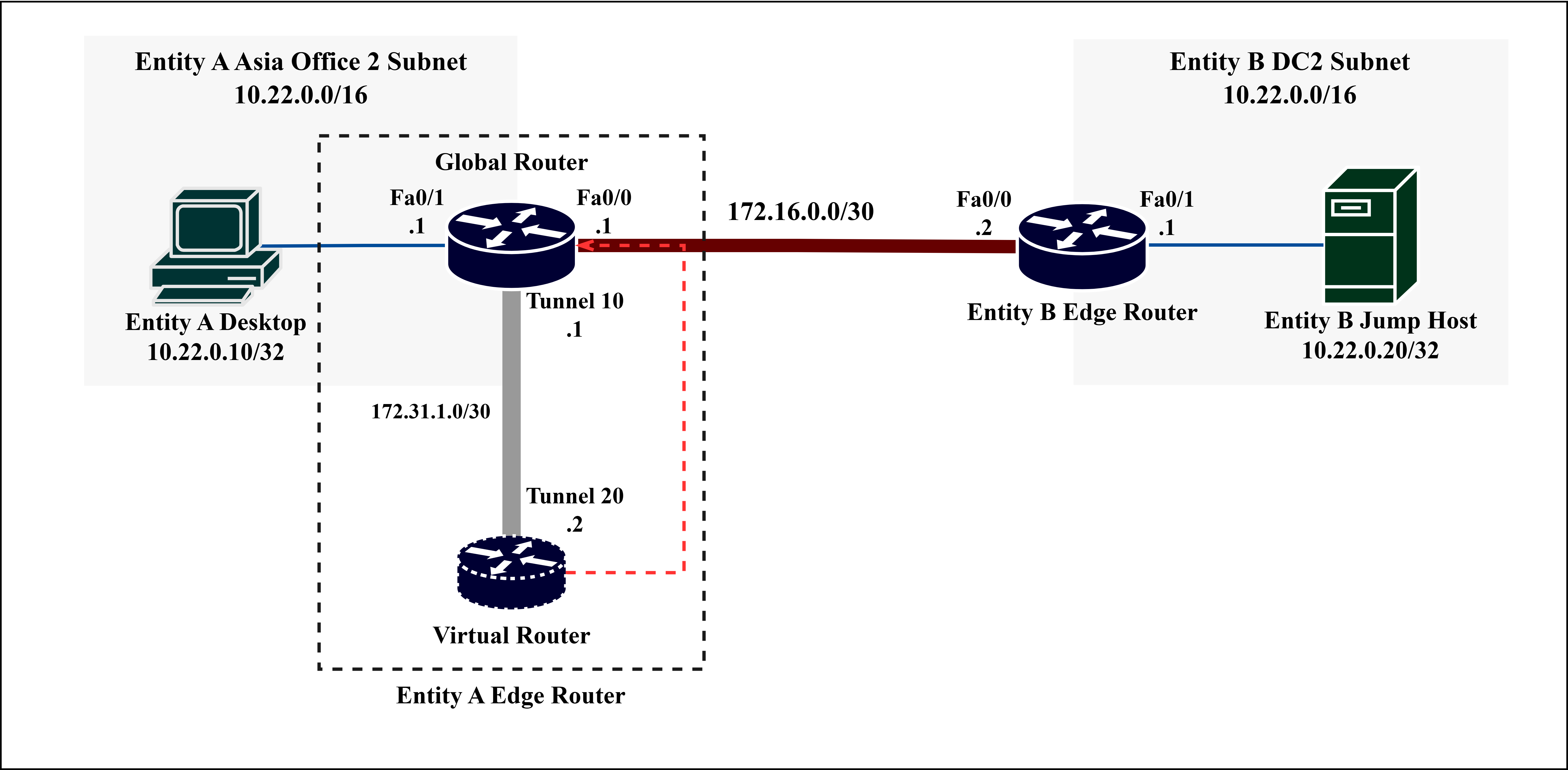

Fig. 5. (a) Simplified Physical Network Topology (b) Simplified Logical Network Topology

Fig. 5 (a) illustrates the simplified physical network topology between Asia Office 2 of Entity A and Data Center 2 of Entity B. Fig. 5 (b) shows the logical diagram of the same network, including the virtual router and logical interfaces to be configured on Entity A’s router. All network address translation occurs at the router of Entity A. The only requirement for the router at Entity B is a route entry to the RFC 6598 translated address of Entity A via the WAN link.

Fig. 6. GNS3 Proposed Network Topology

Fig. 6 above shows the proposed emulated network topology of Fig. 5 on GNS3 using the aforementioned virtual appliances. A C7200-I/O-FE network adapter that houses two FastEthernet interfaces (F0/0 and F0/1) is attached to the Cisco routers to meet the requirements of the simplified network shown in Fig. 5 (a).

Endpoint Network configuration

To truly emulate the network scenario, the endpoints on both entities must have the correct network configuration. This study utilizes the GUI settings of Linux Ubuntu to set the device name and network values. Table 3 below specifies the IPv4 address, subnet, and default gateway configuration of the ens3 Network Interface Card (NIC) on the endpoints of each business entity. The table also defines the hostname (device name) to distinguish the devices in the topology. Although this paper concentrates on Linux configuration, the endpoints can run a different OS (Windows or MAC) as long as it has the correct network settings.

| Entity | Location | Hostname | NIC | IP Address | Subnet | Gateway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Asia Office 2 | desktop-entity-a | ens3 | 10.22.0.10 | 255.255.255.0 | 10.22.0.1 |

| B | Data Center 2 | jumphost-entity-b | ens3 | 10.22.0.20 | 255.255.255.0 | 10.22.0.1 |

TABLE 3 Endpoint Network Configuration

The “net-tools” package adds the ifconfig and route utilities to the Terminal [18]. These commands verify the address and gateway configuration, respectively. Use the sudo apt install net-tools to download and install the “net-tools” package. TABLE 4 (a) and (b) below display the output of the ifconfig and route -n commands, respectively. It verifies that the ens3 interface of desktop-entity-a and jumphost-entity-b have the correct IPv4 address of 10.22.0.10/24 and 10.22.0.20/24, respectively. Furthermore, the route -n table shows the default gateway (0.0.0.0/0) configuration.

| Hostname | NIC | IP Address | Subnet | Broadcast | MTU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| desktop-entity-a | ens3 | 10.22.0.10 | 255.255.255.0 | 10.22.0.255 | 1500 |

| jumphost-entity-b | ens3 | 10.22.0.20 | 255.255.255.0 | 10.22.0.255 | 1500 |

(a)

| Hostname | Dst | Gateway | Genmask | Metric | NIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| desktop-entity-a | 0.0.0.0 | 10.22.0.1 | 0.0.0.0 | 20100 | ens3 |

| '' | 10.22.0.0 | 0.0.0.0 | 255.255.255.0 | 100 | ens3 |

| jumphost-entity-b | 0.0.0.0 | 10.22.0.1 | 0.0.0.0 | 20100 | ens3 |

| '' | 10.22.0.0 | 0.0.0.0 | 255.255.255.0 | 100 | ens3 |

(b)

TABLE 4 (a) ifconfig Output (b) route -n Output

At this stage of the topology setup, the endpoints do not have reachability to their respective default gateway (Cisco 7200 router) since the FastEthernet0/1 interface in Fig.6 does not have any configuration yet. When attempting to reach the IP address of the default gateway, 10.22.0.1, it results in an ICMP Ping failure from both endpoints due to an unreachable destination host.

Cisco Router Initial Configuration

Cisco enterprise routers require the following initial configuration before packets can be routed [8]:

- Cisco router interfaces default to a disabled (shutdown) state and must be enabled;

- there should be an IP address and subnet mask assigned to the interface; and

- the Line and Protocol Status of the interface must be in UP/UP state.

In this study, the Cisco 7200 router has two FastEthernet interfaces, F0/0 and F0/1. Each interface must be enabled, assigned an IPv4 address and mask, and in UP/UP state. The default hostname, R1, must be updated to distinguish the routers easily through their Command-Line interface (CLI) prompt with the use of hostname router-entity-a and hostname router-entity-b commands on the Global Configuration mode of Entity A and B routers, respectively.

The ip address <ipAddress> <subnetMask> interface subcommand assigns an IP address and subnet mask on an interface. For example, to configure the FastEthernet0/1 interface of both routers, enter the ip address 10.22.0.1 255.255.255.0 interface subcommand to assign it an IPv4 address and subnet mask. The interface must be enabled using the no shutdown interface subcommand to move it from its default disabled state. A cable must be attached to the interface and have a matching protocol (Ethernet) to its connecting device before being in a UP/UP state. Fig. 5 (a) illustrates the IP address assignment of the routers’ physical interfaces – specified in Table 5. The show ip interface brief command shows the network configuration and status of the interfaces.

| Hostname | Interface | IP Address | Subnet |

|---|---|---|---|

| router-entity-a | FastEthernet0/0 | 172.16.0.1 | 255.255.255.252 |

| '' | FastEthernet0/1 | 10.22.0.1 | 255.255.255.0 |

| router-entity-b | FastEthernet0/0 | 172.16.0.2 | 255.255.255.252 |

| '' | FastEthernet0/1 | 10.22.0.1 | 255.255.255.0 |

TABLE 5 Router Interface Network Configuration

Configuring the IP address and subnet mask on the interfaces automatically creates directly connected route entries for the 10.22.0.0/24 and 172.16.0.0/30 subnets. Table 6 (a) and (b) below highlight the routing table of router-entity-a and router-entity-b, respectively, using the show ip route command.

| Parent Route | Type | Subnet | Egress Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/8 | Connected | 10.22.0.0/24 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| '' | Local | 10.22.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| 172.16.0.0/16 | Connected | 172.16.0.0/30 | FastEthernet 0/0 |

| '' | Local | 172.16.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/0 |

(a)

| Parent Route | Type | Subnet | Egress Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/8 | Connected | 10.22.0.0/24 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| '' | Local | 10.22.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| 172.16.0.0/16 | Connected | 172.16.0.0/30 | FastEthernet 0/0 |

| '' | Local | 172.16.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/0 |

(b)

TABLE 6 (a) router-entity-a Routing Table (b) router-entity-b Routing Table

Even with the connected routes in place, the endpoints still cannot communicate because both routers do not have a route entry to the remote 10.22.0.0/24 subnet. In the scenario where no address overlap occurred, a static route configured using the ip route <subnet> <subnetMask> <nextHop> command on both the router-entity-a and router-entity-b routers will create a path that allows bi-directional communication between endpoints. However, in this specific case, the router does not add the static route to the routing table since static routes have a higher AD than directly connected routes. For example, in router-entity-a, after entering the ip route 10.22.0.0 255.255.255.0 172.16.0.2, the routing table will still not have any entries to the 10.22.0.0/24 subnet with 172.16.0.2 as the next-hop. Instead, it will retain the directly connected routes in Table 6 (a). The next section of this paper highlights the virtual routing and NAT configuration on router-entity-a to achieve bi-directional communication between the endpoints in the overlapping subnets.

Cisco Virtual Router and NAT Configuration

Fig. 7. Detailed Entity A Router Design

Fig. 7. Detailed Entity A Router Design

A virtual router (VRF) provisioned on the router-entity-a acts as the next-hop router that performs the NAT for traffic destined to the Entity B remote 10.22.0.0/24 subnet. The virtual router allows router-entity-a to distinguish the remote from local networks and make routing possible. While this approach may apply to either or both entities, the implementation will focus on Entity A, making this a feasible solution for entities with minimal access and control over the merging business entity’s router. Fig. 7 above illustrates a detailed level design of how the global and virtual routers connect. Before proceeding with the configuration, the physical interfaces of router-entity-a must first be disabled (shutdown); this stops the NAT Virtual Interface (NVI) from acquiring its IP address from one of the physical interfaces (F0/0 and F0/1). The IP address of a Loopback (Lo) interface is better suited for NVI since Lo interfaces can provide a stable interface with Layer 3 addressing due to its ability to remain UP (active) and independent of the status of any physical interface [19]. NVI, introduced earlier, is automatically created when enabling NAT on a Cisco router [20].

| Name | IP Address | Subnet |

|---|---|---|

| Loopback 1 (Lo1) | 1.1.1.1 | 255.255.255.255 |

| Loopback 2 (Lo2) | 2.2.2.2 | 255.255.255.255 |

TABLE 7 Loopback Interace Network Configuration

After disabling the physical interfaces, provision the Virtual Routing and Forwarding (VRF) or virtual router using the ip vrf <vrfName> command. In this paper, the VRF name is vr-entity-b. Next, create the Loopback interfaces to be used as the tunnel source and destination for the underlay routing of the GRE tunnel between the global and virtual router [21]. TABLE 7 above specifies the Loopback interfaces network configuration. Loopback 1 and Loopback 2 interfaces have the /32 subnet mask making it possible to use any IPv4 address.

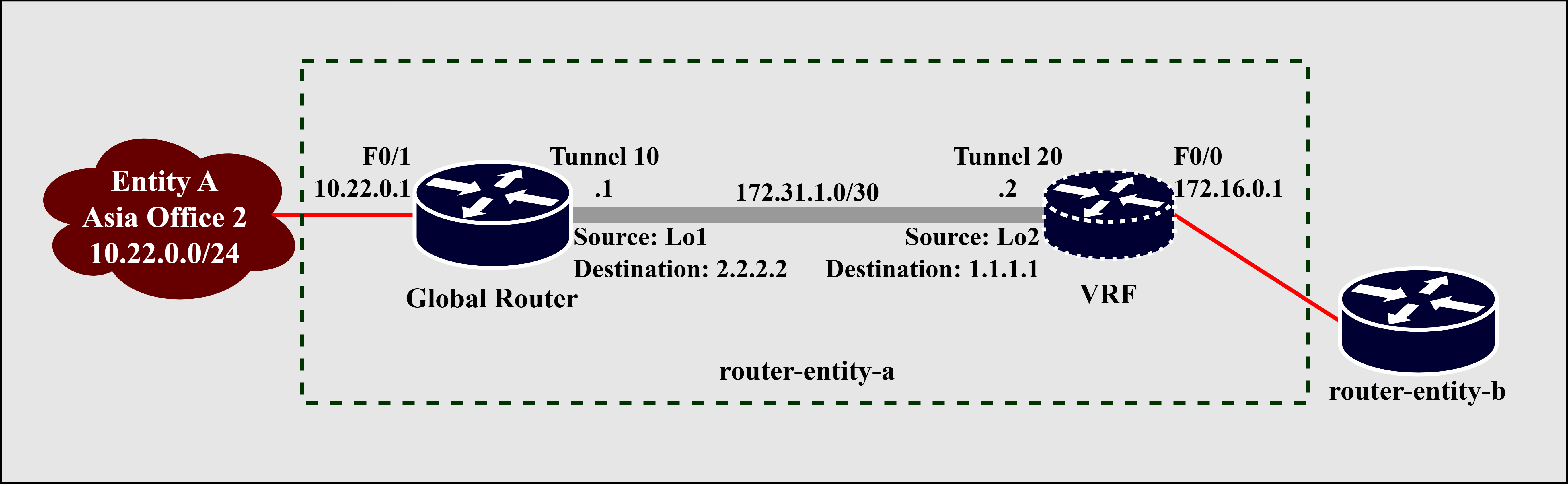

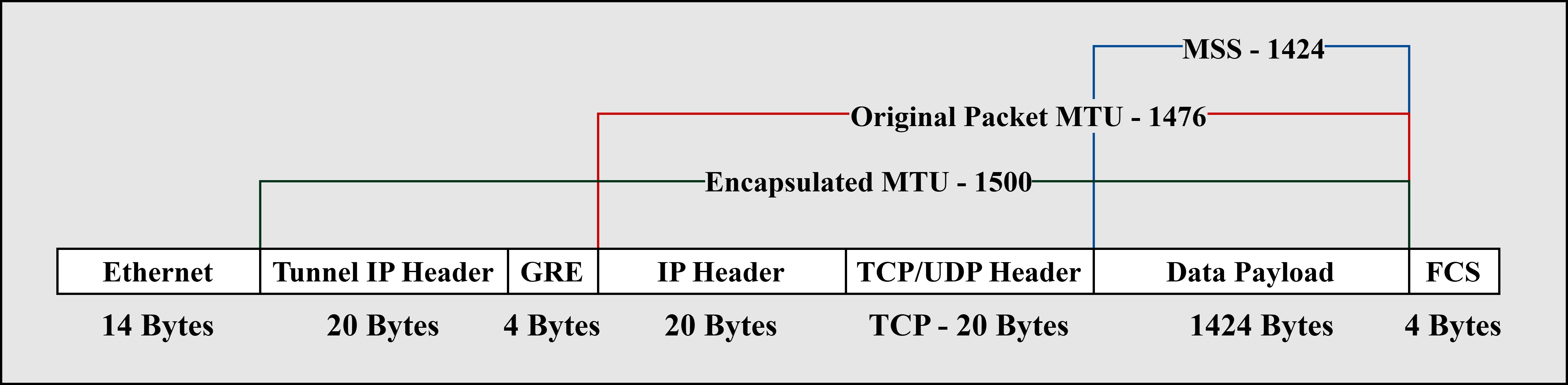

Fig. 8. GRE Encapsulation

Fig. 8. GRE Encapsulation

The global and virtual routers, residing in a single hardware, are treated as separate routers. The tunnel interface creates a logical overlay point-to-point communication path between the two routers by encapsulating the payload packet with a GRE header. An outer IP header containing the IP addresses of Lo1 and Lo2 as source and destination further encapsulates the GRE packet; Fig. 8 illustrates the encapsulation process briefly. Since GRE encapsulates the payload with additional headers, the Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) and Maximum Segment Size (MSS) must be decreased to 1476 Bytes and 1424 Bytes, respectively, from the default 1500 Byte MTU and 1460 Byte MSS [22].

| Router | Name | IP Address | Source | Destination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| router-entity-a | Tunnel 10 | 172.31.1.1/30 | Lo1 | 2.2.2.2 |

| vr-entity-b | Tunnel 20 | 172.31.1.2/30 | Lo2 | 1.1.1.1 |

TABLE 8 Tunel Interface Network Configuration

TABLE 8 above shows the tunnel interface network configuration built upon the two internal loopback interfaces in TABLE 7. The tunnel becomes disabled if no route to the tunnel destination is defined [23]. In this study, Lo1 and Lo2 interfaces are associated with the global router to build directly connected route entries on the global routing table, creating the underlay routing of the GRE tunnel. Alternatively, in Cisco IOS 12 and higher, the Generic Routing Encapsulation Tunnel IP Source and Destination VRF Membership feature [23] allows the configuration of the source and destination of a tunnel to belong to any VRF (and VPN) routing table by adding the tunnel vrf <vrfName> interface subcommand on the Lo1 and Lo2 interfaces.

One end of the tunnel, Tunnel 10, seats on the global router (router-entity-a), and the other, Tunnel 20, on the VRF (vr-entity-b). Like any network interface, each tunnel interface requires an IP address on the same subnet, 172.31.1.0/30, to create a logical point-to-point link for the overlay routing. The tunnel interfaces will switch to the UP state after configuring the underlay and overlay components of the GRE tunnel.

Re-enable the physical interfaces (F0/0 and F0/1) of router-entity-a, then associate Tunnel 20 and FastEthernet0/0 interfaces to the VRF using the ip vrf forwarding vr-entity-b interface subcommand. Fig. 7 illustrates the interfaces association where Tunnel 10 and FastEthernet0/1 belong to the global router, while Tunnel 20 and FastEthernet0/0 belong to the VRF. Note that after associating FastEthernet0/0 to vr-entity-b, it automatically removes any IP address configuration. Therefore, re-configuration of the IP address on FastEthernet0/0 is required. Once the network configuration of FastEthernet0/0 is complete, a directly connected route entry to 172.16.0.0/30 will exist on the VRF (instead of on the global router).

(a)

(a)

(b)

(b)

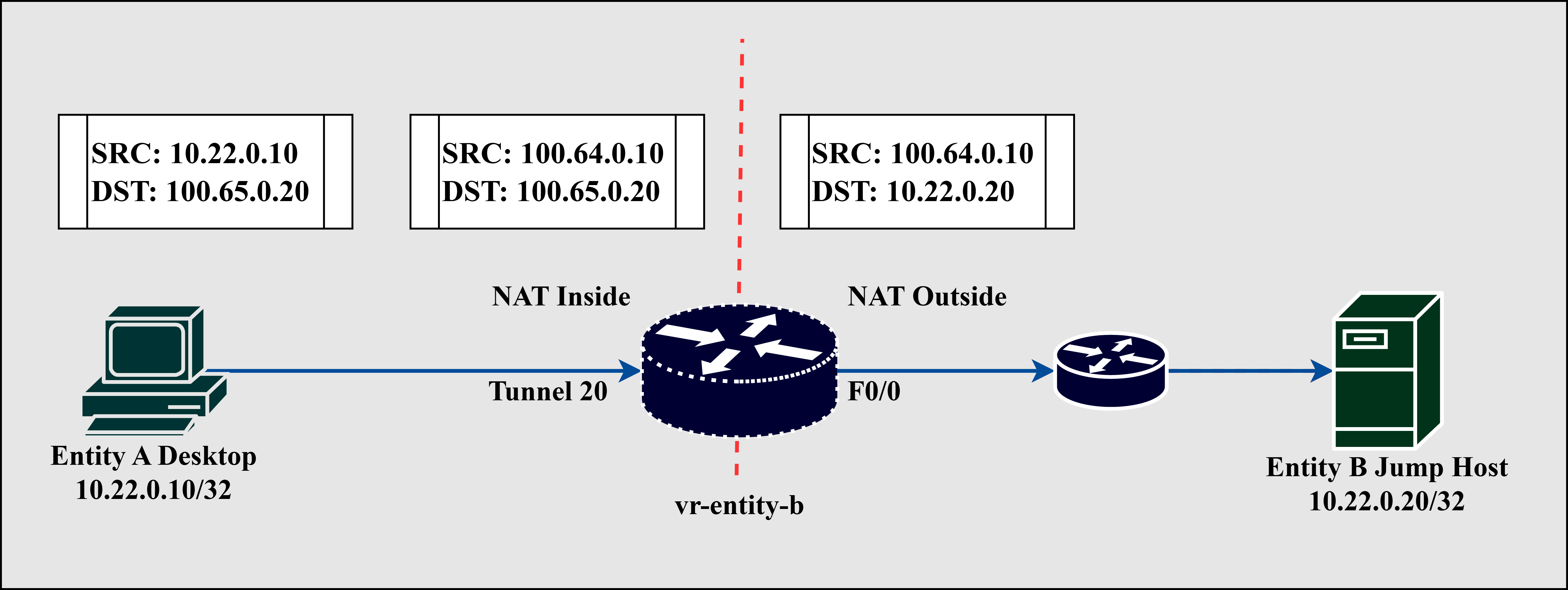

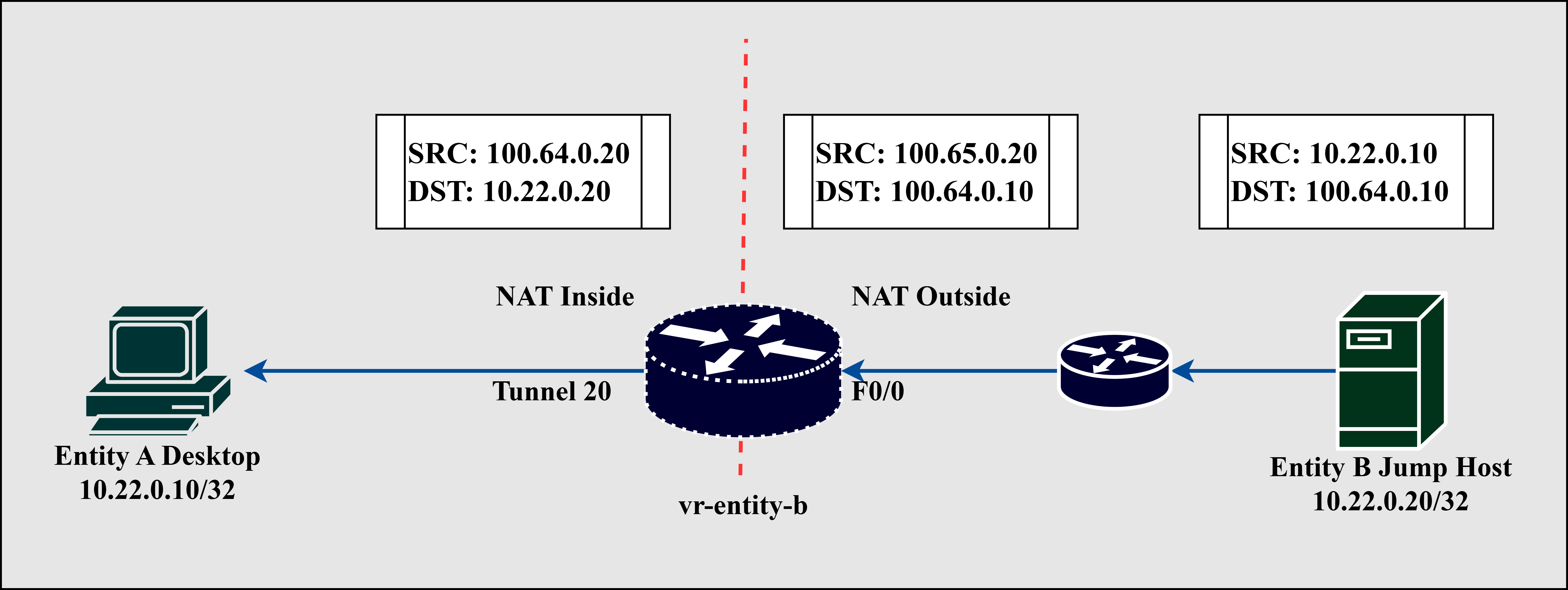

Fig. 9. (a) Outbound NAT (b) Inbound NAT

The VRF performs source and destination NAT for traffic destined to the remote 10.22.0.0/24 subnet of Entity B. The ip nat inside and ip nat outside interface subcommands set Tunnel 20 as the inside interface and FastEthernet0/0 as the outside interface, respectively [8]. Tunnel 20 translates desktop-entity-a IP address from an Inside Local address of 10.22.0.10 to an Inside Global address of 100.64.0.10 and vice versa using the ip nat inside source static <insideLocal> <insideGlobal> command. The FastEthernet0/0 interface translates the jumphost-entity-b IP address from an Outside Global address of 100.65.0.20 to an Outside Local address of 10.22.0.20 and vice versa using the ip nat outside source static <outsideGlobal> <outsideLocal> command. Dynamic NAT and PAT can be implemented instead of Static NAT and will not change the overall results.

Fig. 9 (a) depicts the network address translation of outbound traffic wherein desktop-entity-a attempts to communicate with jumphost-entity-b. Translation of the source address from 10.22.0.10 to 100.64.0.10 (IP address seen by jumphost-entity-b) happens once the packet reaches Tunnel 20, where inside NAT is performed. Before forwarding the packet to router-entity-b, the FastEthernet0/0 interface translates the destination IP address from 100.65.0.20 (IP address seen by desktop-entity-a) to 10.22.0.20, the local IP address of jumphost-entity-b. The reverse occurs when a reply back from jumphost-entity-b is received by router-entity-a, as illustrated in Fig. 9 (b).

| Parent Route | Type | Subnet | Egress Interface / Next Hop |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0.0.0/32 | Connected | 1.1.1.1 | Loopback1 |

| 2.0.0.0/32 | Connected | 2.2.2.2 | Loopback2 |

| 10.0.0.0/8 | Connected | 10.22.0.0/24 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| '' | Local | 10.22.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| 100.65.0.0/24 | Static | 100.65.0.0 | Tunnel 10 |

| 172.31.0.0/16 | Connected | 172.31.0.0/30 | Tunnel 10 |

| '' | Local | 172.31.0.1/32 | Tunnel 10 |

(a)

| Parent Route | Type | Subnet | Egress Interface / Next Hop |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/24 | Static | 10.22.0.0 | Tunnel 20 |

| 100.0.0.0/24 | Static | 100.65.0.0 | 172.16.0.2 |

| 172.16.0.0/16 | Connected | 172.16.0.0/30 | FastEthernet0/0 |

| '' | Local | 172.16.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/0 |

| 172.31.0.0/16 | Connected | 172.31.1.0/30 | Tunnel 20 |

| '' | Local | 172.31.1.2/32 | Tunnel 20 |

(b)

TABLE 9 (a) router-entity-a Global Routing Table (b) vr-entity-b VRF Routing Table

Before the router can properly forward traffic, the correct routing entries must be on the routing table. Table 9 shows the (a) router-entity-a Global Routing table and (b) vr-entity-b VRF Routing table. As stated previously, Lo1 and Lo2 are associated with the global router. As a result, the routes to 1.1.1.1/32 and 2.2.2.2/32 with Lo1 and Lo2 as egress interfaces, respectively, reside in the global routing table. A route entry to the 100.65.0.0/24 subnet, Outside Global address of 10.22.0.0/24 (Entity B), exists via Tunnel 10 in router-entity-a.

On Cisco routers, routing is performed first before NAT when a packet enters from the inside interface (Tunnel 20). Whereas packet entering from the outside interface (FastEtherne0/0), translation takes precedence over routing. As a result, traffic leaving Entity A’s network requires a route to the subnet of the Outside Global address, 100.65.0.0/24, of Entity B. While packets entering Entity A’s network requires a route entry to the subnet of Inside Local address, 10.22.0.0/24, of Entity A. In Table 9 (b), vr-entity-b has routing information for 100.65.0.0/24 with 172.16.0.2 (FastEthernet0/0 of router-entity-b) as next-hop. Furthermore, it has a route entry back to the Inside Local subnet, 10.22.0.0/24, of Entity A via Tunnel 20.

| Parent Route | Type | Subnet | Egress Interface / Next Hop |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/8 | Connected | 10.22.0.0/24 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| '' | Local | 10.22.0.1/32 | FastEthernet0/1 |

| 100.0.0.0/24 | Static | 100.64.0.0 | 172.16.0.1 |

| 172.16.0.0/16 | Connected | 172.16.0.0/30 | FastEthernet0/0 |

| '' | Local | 172.16.0.2/32 | FastEthernet0/0 |

TABLE 10 router-entity-b Routing Table

TABLE 10 shows the required routing entry on router-entity-b to create bi-directional communication to Entity A. Only one static route entry to the Inside Global of Entity A, 100.64.0.0/24, is required. The route entry specifies router-entity-a’s FastEthernet0/0 interface address, 172.16.0.1, as its next hop. The Appendix below provides the complete commands used in router-entity-a and router-entity-b.

Testing Results

After provisioning the VRF, creating the required interfaces, and defining the NAT and routing policies, Entity A and Entity B can now communicate even with their overlapping addresses. Basic reachability between the two endpoints, desktop-entity-a, and jumphost-entity-b, can be confirmed using ICMP Ping. As shown in Fig. 10 below, desktop-entity-a pinged jumphost-entity-b using the ping 100.65.0.20 command. A successful response from 100.65.0.20 indicates that the Layer 1 to Layer 3 components and configuration works.

Fig. 10. ICMP Ping Output

Traceroute is a network diagnostic tool used to track in real-time the pathway taken by a packet IP on an IP network from source to destination, reporting the IP addresses of the ingress interface of each hop [25]. In Fig. 11, using Traceroute, it identified that the packet went to the default gateway (10.22.0.1) of desktop-entity-a, then to the Tunnel 20 interface (172.31.1.2) of vr-entity-b before being routed into router-entity-b FastEthernet0/0 interface (172.16.0.2). Finally, router-entity-b forwarded the packet to the destination, jumphost-entity-b (100.65.0.20). Note that Traceroute always returns the global address [26].

Fig. 11. Traceroute Output

| Inside Global | Inside Local | Outside Global | Outside Local |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100.64.0.10 | 10.22.0.10 | 100.65.0.20 | 10.22.0.20 |

TABLE 11 vr-entity-b NAT Translations

In a Cisco router, show ip nat translations output the active NAT translations. TABLE 11 confirms the expected NAT translations in Fig. 9 performed by vr-entity-b during the ICMP Ping and Traceroute tests. Cisco devices cannot perform packet captures (pcap) on VRFs. As a result, this study cannot provide detailed NAT information through pcap since VRF performs all NAT operations.

References

- Y. Rekhter, B. Moskowitz, D. Karrenberg, G. J. de Groot, and E. Lear, Address Allocation for Private Internets, rfc-editor.org, https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc1918 (accessed October 23, 2022)

- P. Srisuresh, and K. Egevang, Traditional IP Network Address Translator (Tranditional NAT), rfc-editor.org, https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3022 (accessed October 23, 2022)

- W. Odom, CCNA 200-301 Official Cert Guide Volume 2, Hoboken, NJ, USA: Cisco Press, 2020

- V. Goldfeld, M. Stagliano, A. D’Ginto, Mergers and Acquisitions: 2022, corpgov.law.harvard.edu, https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/01/27/mergers-and-acquisitions-2022/ (accessed October 23, 2022)

- J. Weil, V. Kuarsingh, C. Donley, C. Liljenstolpe, and M. Azinger, IANA-Reserved IPv4 Prefix for Shared Address Space, rfc-editor.org, https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc6598 (accessed October 24, 2022)

- Google, Google IPv6 Statistics, google.com, https://www.google.com/intl/en/ipv6/statistics.html (accessed October 24, 2022)

- W3Techs, Usage Statistics of IPv6 for Websites, w3techs.com, https://w3techs.com/technologies/details/ce-ipv6 (accessed October 24, 2022)

- W. Odom, CCNA 200-301 Official Cert Guide Volume 1, Hoboken, NJ, USA: Cisco Press, 2020

- A. D’mello, Why IPv6 Adoption is Still Light Years Away, iot-now.com, https://www.iot-now.com/2020/07/22/104012-why-ipv6-adoption-is-still-light-years-away/ (accessed October 24, 2022)

- F. Andrew, IPv4 Subnetting Best Practices, networkcomputing.com, https://www.networkcomputing.com/networking/ipv4-subnetting-best-practices (accessed October 29, 2022)

- Fortinet, Azure routing and network interfaces, docs.fortinet.com, https://docs.fortinet.com/document/fortigate-public-cloud/7.0.0/azure-administration-guide/609353/azure-routing-and-network-interface (accessed October 29, 2022)

- Networkers-Online, How routers select best routes ?, networkers-online.com, https://www.networkers-online.com/p/how-routers-select-best-routes (accessed October 30, 2022)

- Cisco, What Is Administrative Distance?, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/docs/ip/border-gateway-protocol-bgp/15986-admin-distance.html (accessed October 30, 2022)

- ComputerNetworkingNotes, Connected Routes and Local Routes Explained, computernetworkingnotes.com, https://www.computernetworkingnotes.com/ccna-study-guide/connected-routes-and-local-routes-explained.html (accessed October 30, 2022)

- Tailscale, What are these 100.x.y.z addresses?, tailscale.com, https://tailscale.com/kb/1015/100.x-addresses/ (accessed November 04, 2022)

- GN3, Getting Started with GNS3, docs.gns3.com, https://docs.gns3.com/docs/ (accessed October 30, 2022)

- T. Bagci, What is GNS3? | What Does it Do?, sysnettechsolutions.com, https://www.sysnettechsolutions.com/en/what-is-gns3/ (accessed October 30, 2022)

- B. Eckenfels, and P. Blundell, net-tools Overview, wiki.linuxfoundation.org, https://wiki.linuxfoundation.org/networking/net-tools (accessed November 02, 2022)

- Cisco, Configuring Virtual Interfaces, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/td/docs/ios/12_4/interface/configuration/guide/inb_virt.html (accessed November 05, 2022)

- Cisco, NAT Virtual Interface, San Jose, CA, USA: Cisco Systems, 2005

- Cisco, Interface and Hardware Component Configuration Guide for Cisco CRS Routers, IOS XR Release 6.7.x, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/td/docs/routers/crs/software/crs-r6-7/interfaces/configuration/guide/b-interfaces-hardware-component-cg-crs-67x/b-interfaces-hardware-component-cg-crs-66x_chapter_010010.html (accessed November 05, 2022)

- J. Langemak, The basics – MTU, MSS, GRE, and PMTU, dasblinkenlichten.com, https://www.dasblinkenlichten.com/the-basics-mtu-mss-gre-and-pmtu/ (accessed November 05, 2022)

- Cisco, Generic Routing Encapsulation Tunnel IP Source and Destination VRF Membership, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/td/docs/routers/10000/10008/feature/guides/122_31sb5/fs_gripvrf.html (accessed November 05, 2022)

- Cisco, NAT Order of Operation, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/docs/ip/network-address-translation-nat/6209-5.html, (accessed November 06, 2022)

- ThousandEyes, Traceroute, thousandeyes.com, https://www.thousandeyes.com/learning/glossary/traceroute (accessed November 06, 2022)

- Cisco, Network Address Translation (NAT) FAQ, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/docs/ip/network-address-translation-nat/26704-nat-faq-00.html (accessed November 06. 2022)

- Cisco, Verify and Troubleshoot Basic NAT Operations, cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/docs/ip/network-address-translation-nat/8605-13.html (accessed November 06, 2022)

- Cisco, Network Management Configuration Guide, Cisco IOS XE Everest 16.6x (Catalyst 9300 Switches), cisco.com, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/td/docs/switches/lan/catalyst9300/software/release/16-6/configuration_guide/nmgmt/b_166_nmgmt_9300_cg/b_166_nmgmt_9300_cg_chapter_0110.html (accessed November 06, 2022)